La Organización Mundial de la Propiedad Intelectual (OMPI) o WIPO (World Intellectual Property) foro mundial en materia depropiedad intelectual (P.I.), se estableció por el Convenio de la OMPI, de 14 de julio de 1967, entrando en vigor el 26 de abril de 1970. Está formada por 189 Estados miembros y sus funciones en materia de propiedad intelectual son extraordinariamente relevantes, ayudando a los gobiernos, empresas y a la sociedad a obtener beneficios de la P.I.

Entre las funciones que desempeña subrayamos:

-

Contribuye a que las normas internacionales de P.I. sean equilibradas;

- Presta servicios mundiales en favor de la protección de la P.I. y la solución de controversias;

- Ofrece infraestructura técnica para conectar los sistemas de P.I. y compartir conocimientos;

- organiza programas de cooperación y fortalecimiento de las capacidades de modo que todos los países puedan utilizar la P.I. y, de su mano, conseguir también un mayor desarrollo económico, social y cultural;

- es una fuente mundial de referencia para obtener información sobre P.I.

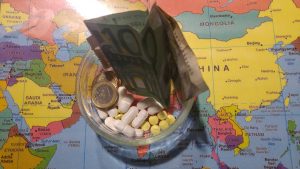

Además de todas estas funciones, de vital importancia, cabe hacer hincapié en una nueva iniciativa de gran calado en los países en desarrollo, y que es absolutamente loable, cual es el Programa de Asistencia a Inventores (PAI) con la que se presta ayuda a inventores con escasos recursos económicos, cooperando con ellos en la solicitud de patentes.

Este Programa consiste en poner en contacto a inventores y pequeñas empresas que carecen de los recursos suficientes para patentar sus innovaciones con abogados especializados en propiedad intelectual (P.I.) dispuestos a trabajar altruistamente, sin cobrar, para ayudar a los inventores en el proceso de solicitud de patentes. La presentación oficial del Programa de Asistencia a Inventores (PAI) se realizó el 17 de octubre de 2016, después de experiencias piloto llevadas a cabo con éxito en Colombia, Marruecos y Filipinas.

Con el ánimo de difundir el conocimiento sobre la P.I., los Estados miembros de la OMPI, en el año 2000, eligieron el 26 de abril para celebrar el Día Mundial de la Propiedad Intelectual, conmemorando así el día de la entrada en vigor de dicho Convenio. Desde entonces, cada año este día se aprovecha en todo el mundo para informar sobre los denominados derechos de propiedad intelectual (patentes, marcas, diseños industriales, derecho de autor) e intercambiar experiencias entre las personas interesadas en los temas de P.I., insistiendo en el importante cometido de la OMPI en este sector.

- Cada año se fija un lema para dicha conmemoración. El de este año es “La innovación mejora la vida”. Y ello porque, como gráficamente se señala desde la OMPI (aquí) y en concreto en el mensaje del Director General Francis Gurry, la innovación transforma los problemas en progreso. En palabras suyas:

- “En la campaña del Día Mundial de la Propiedad Intelectual del presente año festejamos la innovación y la manera en que mejora nuestras vidas. También rendimos homenaje a todos quienes asumen riesgos, a aquellas personas que se han atrevido a esforzarse por lograr cambios positivos a través de la innovación”.

Como destaca la OMPI, de manera gráfica:

Fotografía de página de Facebook de la OMPI.

- “En el Día Mundial de la Propiedad Intelectual de 2017 se celebrará esa fuerza creativa. Analizaremos las mejoras que han traído a nuestra vida algunas de las innovaciones más extraordinarias del mundo y cómo contribuyen las nuevas ideas a afrontar retos mundiales comunes, como el cambio climático, la salud, la pobreza yla necesidad de alimentar a una población en constante crecimiento.

- Estudiaremos la contribución que hace el sistema de propiedad intelectual a la innovación mediante la atracción de inversiones, la recompensa a los creadores, los estímulos para que desarrollen sus ideas y los mecanismos para garantizar que sus conocimientos están disponibles de manera gratuita a fin de que los innovadores del futuro puedan aprovechar las nuevas tecnologías del presente”.

En nuestro país, con este motivo, la Oficina Española de Patentes y Marcas intensificará su programa de actividades de difusión de la P.I. y, haciéndose eco de la recomendación de la OMPI, anima a participar a particulares y organizaciones a través de Facebook y Twitter, utilizando la etiqueta #worldipday. Más información en http://www.wipo.int/ip-outreach/es/ipday/,